1 Communciation Models

1.1 Aristotle and Lasswell

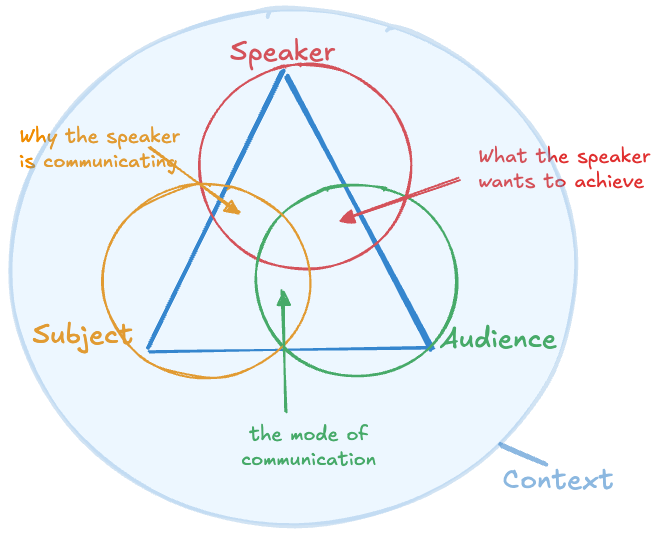

There is no shortage of theoretical models for how communication takes place. One of the oldest models dates back to the fourth century BC and the Greek philosopher Aristotle . Aristotle studied rhetoric, the art of persuasion. What is called the rhetorical situation (Figure 1.1) describes a triangle between communicator (speaker), audience, and a subject that is conveyed.

In modern times, the rhetorical situation was enhanced and embellished by acknowledging that the context in which the communication takes place also matters. But the basic structure remains the same: someone wants to persuade an audience with information (a subject).

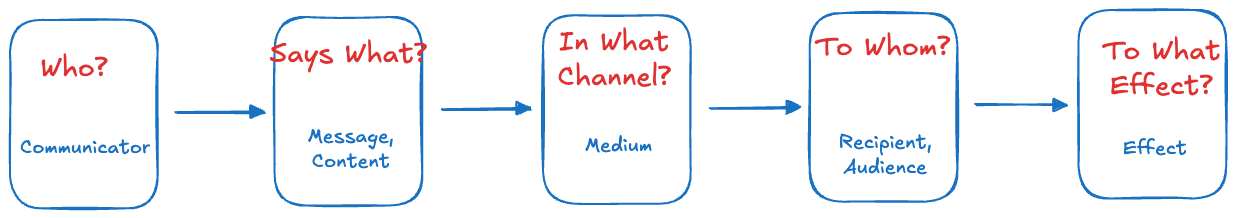

A model with a linear structure that conveys related ideas is due to political scientist Harold Lasswell, who published a simple communication model in 1948 (Figure 1.2). The Lasswell model simply asks the question Who Says What in What Channel to Whom and to What Effect?

Each question in the Lasswell model is assigned to its own field of inquiry. For example, the question In What Channel? is the topic of media analysis, the question Says What? is the topic of content analysis. Critics of the Lasswell model cite the lack of context, and the linear structure that does not accommodate feedback. Like Aristotle’s model, it is simple enough for us to make progress with a theoretical understanding of communication without getting bogged down in the minutiae.

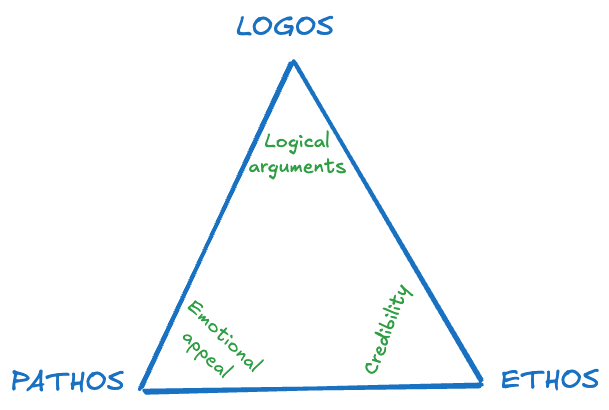

The triangle in Aristotle’s rhetorical situation is accompanied by the rhetorical triangle in Figure 1.3. In order to be persuasive, communication must have the three appeals in the figure. Logos appeals through facts and logical arguments, ethos through character and credibility of the speaker, and pathos appeals through emotions. Kuchel and Rowland (2023) refers to the logos approach as “aiming for the head, not the heart” and the pathos approach as “aiming for the heart, not the head”.

Effective communication does not necessarily have the three appeals in equal measure, but it has elements of all three appeals in some measure. We are not being influenced by a message if the information or the communicator lacks credibility. Unless we care about the subject and are willing to get emotionally engaged, the information falls flat. And information that does not make any sense is unlikely to be persuasive.

In technical fields we tend to pay too much attention to Logos, thinking (or hoping) that information presented with logically sound arguments will automatically stick and persuade. We have all come to know the dry and boring technical presentations delivered without passion and emotional appeal. Double-whammy if the presenter does not have or does not establish credibility of the information or themselves and delivers without personality. Attending a scientific conference one could conclude that this style of presentation is so common; it is almost to be expected. it does not have to be this way.

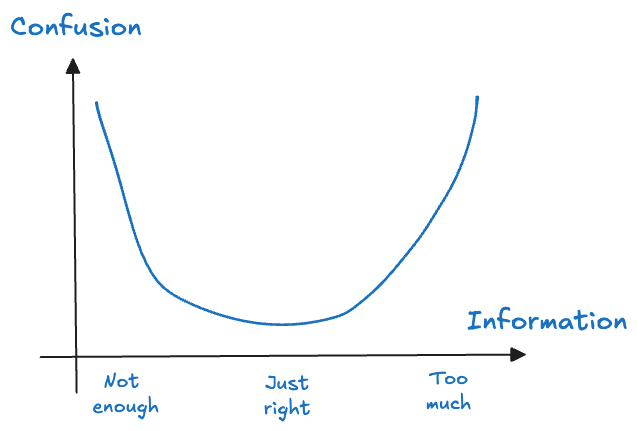

Communicating too much information that the audience cannot process and communicating too little information to make it worthwhile for the audience to pay attention ends up having the same effect: confusion (Figure 1.4).

Example: Boring Presentation

Watch the following 3:28 minute video on presentation principles keeping in mind the rhetorical triangle and the Lasswell model of communication.

Is the information presented logically sound?

Is the presenter and the information credible?

Are you emotionally engaged as a viewer?

Can you answer the questions in the Lasswell model: Who says what in what channel to whom to what effect?

For the 3 1/2 minutes you spent with the video, did you get too little or too much information about presentation principles?

How could the information be communicated more persuasively?

Speakers that are passionate about the subject are engaging and are more authentic and believable compared to the dry, dispassionate communicator. A passionate communicator makes themselves vulnerable by conveying their love for the subject. This opening-up signal is received by the audience which in turn is allowed to open up. The vulnerability loop, as it is called, is an effective tool to make connections and build trust—it presses emotional buttons. So do joy and laughing.

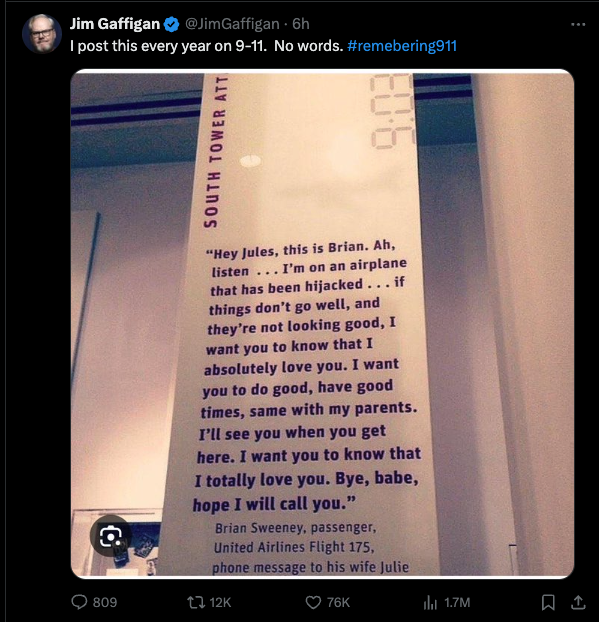

Emotional connections are powerful. As an example, take the following communication by actor and comedian Jim Gaffigan. He repeats the same tweet (Figure 1.5) on every anniversary of 9/11.

1.2 Forms of Communication

Formally, we distinguish the following forms of communication:

- Verbal. Communicating through words, mostly spoken words (oral communication)

- Visual. Involves the use of graphics, signs, video, and so on.

- Written. Conveying information in written form, whether it is an email, letter, memo, contract, report, or text message. It is a form of verbal communication because writing uses words.

- Nonverbal. Communication without words, using body language, facial expression, nonverbal cues, and so on.

We’d like to add another form of inter-personal communication that is often overlooked and plays a critical role in today’s society:

- Listening. In particular active listening with focus on the other person and intent to understand what they are trying to convey.

Speaking, Visualizing, Writing

Imagine giving a presentation in a conference room to a group of business leaders. You are presenting for the data science team the results of the latest A/B test experiments on website designs. The presentation will likely draw on several communication modes: you speak words, use visual aids to support your points and to provide context, and written information the audience reads.

Speaking, drawing (visualizing), and writing are the activities associated with verbal, visual, and written forms of communication. A presentation is a combination of these basic communication activities.

Some principles of communication, such as the rhetorical triangle, or the recommendation to strive for character, brevity, clarity, and honesty, apply to all modes and forms of communication. They also have their specific principles and challenges. Separate chapters in Part III, Practice of Communication, are dedicated to speaking, visualization (drawing), and writing. Here, we explore their relative importance in communicating content.

All humans and human groups have language itself or the capacity for language. The time when language developed varies by source but we can roughly say that we communicated with language and diversified language about 100,000 years ago. This is significant because it predates other modes of communication by tens of thousands of years

After the invention of language, the next significant innovation in communication was drawing. The first graphical depictions found in caves date back to about 64,000 years ago. The first figurative cave drawing depicting a bovine was dated to about 40,000 years ago. In addition to transferring knowledge through oratory we now used imagery to tell a story (Figure 1.7).

It took more than 35,000 years after that for the first writing to appear. One of the oldest known writings is Sumerian cuneiform in the Kish tablet from about 3,500 BC (Figure 1.8). The tablet depicts hands and feet, but also numbers. The pictography in early form of text shows its evolution as a communication tool from drawing.

Among the more recent inventions in communication are newspapers, blogs, vlogs, images, video, audio, text messages, email, Slack, and social media posts. And let us not forget 1987: the first release of Microsoft PowerPoint. “Yes, and proud we are of all of them” (The Big Lebowski).

Why bother with all that in the context of team-based data science communication?

Our brains are most wired for earlier forms of communication and least wired for more recent forms. The most effective way of communicating is by telling a story, as if you were sitting around a campfire, with the audience focused entirely on the speaker. It is unlikely that you will communicate data science ideas sitting around a fire—kudos if that happens to you and also, um, get a life. However, by applying principles of storytelling, knowledge transfer to the audience is much more effective. These principles can be brought to bear whether you deliver an extemporaneous speech, write an email to a collaborator, or produce a visual essay.

After speaking, the second most effective means of communication is visually. Graphics, plots, and drawings are never the story themselves, but they help you get the story across. Memorable communication supports spoken words with visual appeal.

Less effective in presentations are written words. Although we have trained ourselves to consume information by reading, in the throws of a presentation we are more likely to connect with information we hear and see, than information we read.

The Greek philosopher Plato, a student of Socrates and a teacher of Aristotle, felt strongly about the power of oratory. In Phaedrus, Plato presents through a dialog between his teacher Socrates and Phaedrus. His Socrates says

he who has knowledge of the just and the good and beautiful […] will not, when in earnest, write them in ink, sowing them through a pen with words, which cannot defend themselves by argument and cannot teach the truth effectually

and

You know, Phaedrus, that is the strange thing about writing, which makes it truly correspond to painting. The painter’s products stand before us as though they were alive. But if you question them, they maintain a most majestic silence. It is the same with written words. They seem to talk to you as though they were intelligent, but if you ask them anything about what they say from a desire to be instructed they go on telling just the same thing forever.

Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal communication are the ways in which we convey and receive messages and information by other means than speaking, visualizing, or writing. Nonverbal communication is both intentional and unintentional, many speakers are not aware of some of the nonverbal cues that enhance or detract from the message.

Examples of nonverbal cues in communication include body language, facial expression, clothing, posture, eye contact, touch, loudness and tone of voice, use of space, movement, smell, and nonverbal vocalizations such as sighing, scoffing, laughing, crying. Nonverbal messages are also produced by the overall setting, for example, use of space, time, and silence.

One of the executives on the leadership team was known for their excessive nonverbal contributions to meetings. While others were speaking, he would shake his head, sigh, fidget uncomfortably in the chair, frown, scowl, scoff, and laugh under their breath. The nonverbal cues were meant to draw attention away from whoever was speaking, to associate their contributions with negative emotions, and to show disapproval.

The popularity of the executive, which was not stellar to begin with, suffered greatly from the nonverbal behavior. The support from the rest of the leadership team eroded, which reduced the executive’s effectiveness in the role. The rest, as they say, is history.

The 7% myth

When forms of communication are discussed, you will encounter the percentages 55, 38, and 7%. These refer to the importance of nonverbal body language (55%), tone of voice (38%), and the actual words spoken (7%). Since tone of voice is also nonverbal, these percentages would suggest that more than 90% of communication is nonverbal. Can this be true?

Think of reading the text of the Gettysburg address or Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I have a Dream” speech. Would we really grasp only 7% of what the authors meant if we have access to the words only?

Yes, nonverbal communication is important—extremely important, and its impact is often under-estimated. The problem with the 55/38/7 numbers is that they apply to a specific experiment and situation, when the verbal and nonverbal channels do not match. If the attitude of the words we are speaking and the attitude we communicate through body language do not match, then the postural component dominates the attitude that is inferred. In other words, if your nonverbal communication contradicts the message, the contradiction will win out.

When someone yells “I am fine” while writhing in pain on the ground with a broken bone sticking out of their leg, we believe the nonverbal part of the communication. They are not fine.

The takeaways:

- Giving nonverbal cues that contradict the message will derail your communication.

- Nonverbal communication that supports the message is very important, but it does not carry 90% of the weight.

Here is an entertaining video about the importance of nonverbal communication. Unfortunately, Dr. York perpetuates the myth that only 7% of communication is carried by the words we say.

The first impression

Thin-slicing is a term from psychology to describe finding patterns and shaping opinions based on a small amount of information, a thin slice of the possibly available information. Research has shown that we are surprisingly good at thin-slicing, the attitudes formed based on small amounts of information are often similar to those formed based on having access to more information.

Thin-slicing occurs when we first meet someone. We initially form opinions about them, taking a quick snapshot of who we think they are. In a study of TED talks, discussed here, the authors investigated what makes some TED talks go viral while others get many fewer views. After all, TED talks in general are great talks, with interesting content delivered by well rehearsed and credible speakers.

The research showed that we are thin-slicing speakers almost immediately based on nonverbal cues. Are they credible and competent? Are they charismatic? Are they friendly? The sobering result is that opinions about the speaker, and by extension about the talk, were formed largely during the first seven seconds. To test the result, the study compared the ratings of audiences who watched only the first seven seconds of the talk and those who watched the full talk. Which speakers and talks the audiences overall liked and disliked matched. As soon as the person takes the stage we thin-slice and form an opinion “I think I am going to like this talk”.

Here are a few other fascinating results from the study of TED talks:

It’s not what you say, it’s how you say it. Audiences who watched the speakers on mute rated the talks almost exactly with respect to overall rating, speaker intelligence, charisma, and credibility as audiences who watched the talk with sound

More hand gestures is better. The popularity of the talk increased with the number of hand gestures a speaker makes.

Scripts kill your charisma”. Talks are rated higher when the speaker shows more vocal variability. Working with scripts or teleprompters works against variety in vocal impressions. Also, ad-libbing is rated higher than staying on script.

Smiling makes you look smarter. The more speakers smiled, the higher their perceived intelligence rating.

More on the Do’s and Do Not’s of nonverbal cues in practicing communication in Chapter 8.

1.3 The Audience

Confronted with communication the audience has three choices: ignore it, engage with it, or respond to it (Longnecker 2023). Being ignored is not what you are after when communicating. To increase engagement and response, you must consider the audience. Who are you communicating to? What are their background, circumstances and motivation? What is their interest level? Why would they care?

All audiences are comprised of individuals and it helps to imagine what the average audience member is like as well as the variability among them. The checklist in Longnecker (2023) includes asking yourself the following questions about audience members

- What are their relevant values and beliefs?

- Do they have existing awareness and attitudes about the topic?

- Will they be receptive to the information?

- What is their knowledge about the topic?

- Will they have the skills, resources, and support to act upon the information?

As chief technology officer (CTO) of a technology company I was often asked about emerging technologies and what they meant for our business, for our customers, or for society in general. Cognitive computing, deep learning, internet of things, artificial intelligence, blockchain, quantum computing, NoSQL databases are some of the topics I had to speak to.

When preparing for those conversations it was helpful to imagine four archetypes of audience members:

My mother. How would you explain the topic to someone with limited technical knowledge—sorry, mom. The goal of the communication is to convey the basics of the technology and anchor it correctly to her view of the world.

A media reporter. Charged with having to produce material on the topic, I want to inform them and convey a position if necessary. There is limited opportunity to ask questions, for example to establish their knowledge level, and limited time of engagement. What is the quotable sentence that they will write down, record, and reproduce?

An industry analyst. These folks tend to have (strong) opinions on everything although they have limited time to learn and grasp new technologies. Tech evolves more quickly for anyone to become expert on all aspects of the technology in a given field. If the analyst has already formed an opinion about a tech topic I want to convey my view and establish how they differ or agree—and why.

A technical expert. Talking to someone who knows much more about the topic than myself, I want the time they spend with me on the subject to be valuable to both sides. The goal is to learn something and at the same time not to waste their time. Communication has to establish for the benefit of the expert the depth of my understanding so they can build on that foundation.

Example: Blockchain Technology

Blockchain is a type of database technology that allows the secure sharing of information, for example financial transactions.

Blockchain is essentially an append-only ledger that is made secure by distributing copies of the ledger across a network. This makes it difficult to tamper with the information as one would have to modify all copies of the ledger. Blockchain is not an application, but can be the backbone of the next generation of applications on the internet.

We can view blockchain as another form of distributed database technology, but that would not do justice to most distributed databases. As an append-only system it is fairly simple. The more important question in my opinion is which applications will be built on blockchain technology. As in other areas such as the Internet of Things (IoT), it is rather difficult to replace incumbent approaches that are only somewhat broken. I expect blockchain technology to be most successful in new application areas where safe, distributed transactions are key. For example, rather than replacing the SWIFT international payment system, blockchain can help build systems for micropayments for online content creators.

My motivation to examine blockchain technology is from the standpoint of building applications for cryptographically safe transactions. While the distributed nature of the chain helps to provide security, I am wondering whether that feature inhibits applications where transaction speed is also essential. I am curious about your views on tradeoffs with blockchain technology.

There are other ways to categorize audiences that can be helpful in tailoring communication. For example, by their interest level.

Interested and appreciative. An easy audience to communicate to; the members are motivated and often self-selected. Giving a talk at a scientific conference to like-minded “birds of a feather” or hanging out with other data scientists is where you can find such an audience.

Uninterested. You need to motivate the audience in order to engage with your communication. What is in it for them, how can you make the information relevant for them?

Skeptical or polarized. Imagine giving a talk about climate change, immigration, or vaccination to a randomly chosen audience. The audience members will typically be interested in the topic but with firmly held beliefs. What are the barriers that need to be overcome to perceive information that might be at odds with their beliefs? Successful communication aligns with the values of the audience. In audiences that are misaligned with the communicator or that exhibit diversity in values and beliefs, communication is more challenging. Mindful communication that considers different perspectives is more effective than patronizing communication.

1.4 The Curse of Knowledge

Tappers and Listeners

Heath and Heath (2007) describe an experiment at Stanford University in the 1990s by Ph.D. student Elizabeth Newton where subjects were assigned to two roles. A tapper was asked to chose a song from a list of well-known tunes—think “Star Spangled Banner” or Happy Birthday to You”. They then tapped the rhythm of the tune to a listener who had to guess the song based on the rhythm.

It turns out that listeners guessed correctly only 3 of 120 tapped songs, a paltry 2.5% success rate. Yet when the tappers were asked to predict the chance that listeners would identify the tune, they guessed a 50% success rate.

This phenomenon is known as the curse of knowledge or the expert’s curse.

A knowledgeable person has a difficult time to reconstruct what a person lacking that knowledge would think. If you are better informed, it is difficult to correctly anticipate the judgement of lesser informed people. The tappers had knowledge of the song they were tapping out, literally having it play in their head. Knowing what the outcome of the experiment ought to be—I am tapping “Happy Birthday to You”—made the outcome in the tapper’s mind more predictable than it actually was. The poor listeners did not have access to that information and had to reconstruct the tune from only the rhythmic tapping.

We have a strong tendency to unknowingly assume that others know what we know or that it would be easier to learn it than it actually is or that others can learn concepts in the same way that the concepts make sense to us now.

IRL (In Real Life)

This experiment plays out in real life millions of times every day.

When a university professor teaches expectations of random variables they do it armed with the knowledge of hundreds of applications and mathematical tricks an experienced statistician brings to bear. That is the tune in their head; they cannot imagine the state of their own mind before they first learned about expected values. The curse of knowledge is also at play when you ask a teacher whether the students are learning. The way the teacher conveys material, based on already knowing it, may not be best for those who lack the teacher’s knowledge.

When a software engineer writes documentation for the features of the latest product release, they are equipped with deep inside knowledge about the software. They have a difficult time imagining what it is like for a user to experience the software for the first time. Software user interfaces that are intuitive to the engineer who developed it but are counterintuitive and complicated for everyone else are an example where the curse of knowledge clouds the judgment.

A company executive cannot unlearn what they know about the nature and conventions of the business. When crafting communications to employees they cannot imagine what it is like not knowing the ins and outs of market capitalization or maximizing shareholder value.

A data scientist presents to company executives the result of developing over the last three months a new customer churn model based on data collected from the nascent SaaS (Software as a Service) business of the company. The data scientist knows the ins and outs of the data used for model development as well as the pros and cons of the considered models. Because the various models had tradeoffs the ultimate churn prediction is based on a heterogeneous ensemble of models from four families. In the presentation the data scientist assumes that the executives are familiar with customer data from SaaS business because he is very familiar with it. The executives cannot relate to the input or output of the work and cancel the project.

Using statistical jargon that the audience is unfamiliar with is another example of the curse of knowledge. Can you imagine how a brain processes the information that is not trained in significance levels, learning rates, or cross-entropy loss?

Knowing your audience means putting yourself into the frame of mind of someone without the expert knowledge you bring to the conversation. In order to be effective at transferring knowledge, you need to know what the vessel you are transferring knowledge into looks like.

What Can Be Done About It?

How can we alleviate the effects of the curse of knowledge?

The first piece of advice is to have empathy for your audience but that is easier said than done. Empathy is often described as “walking in someone else’s shoes”, “seeing the world through someone else’s eyes”. As Brené Brown instructs, you cannot put on some magic glasses and lens the world through someone else’s eyes. You cannot walk in someone else’s shoes. Empathy means to acknowledge that someone has different experiences and views from yours. Rather than trying to walk in someone else’s shoes, empathy is about acknowledging that those shoes exists—and that they do not fit your feet.

Fighting the curse of knowledge through empathy is a great start. While it is valuable to acknowledge that the less knowledgeable state of mind is different from ours, we are limited by not being very good at figuring out what exactly the less knowledgeable state of mind looks like—in the audience and in ourselves.

As communicators we also need to have empathy for ourselves, as we were in the less knowledgeable state before we became experts at the topic we are communicating. Unfortunately, we are also not good in empathizing with our past selves in less knowledgeable states. This inability stems from being anchored in a state of mind full of hindsight created by the receipt of knowledge (Fischhoff 1975).

In preparing material, ask for feedback. What resonated with the audience? What did they not understand? Reread your own material after some time. If it is not clear what you meant by something or why you wrote a passage the way you did, how can you assume that the audience will understand what you meant?

Software engineers experience this phenomenon the hard way when they do not document code when they write it. At the time, it is perfectly clear to them how the code works and why it is written the way it is. Six months removed from it they wonder what in the world this code is supposed to do, how it works, and who wrote it.

The next piece of advice to defeat the curse of knowledge is to use concrete and relatable language to describe complex things. Avoid abstract language and jargon. Use analogies (something is like something else, “life is like a box of chocolates”) and metaphors (compare two things directly, “time is money”) to communicate complex topics. Metaphors and analogies make the unfamiliar seem familiar, they ease the audience into a topic, break down barriers, and provide a comforting baseline understanding.

Rather than trying to figure out what you meant by random error, referring to noise in the system allows the audience to connect a statistical concept to real-life concept and to follow along. Unstructured data can turn into doctor’s notes or online buzz. Nonlinear optimization can become finding, a neural network is somewhat brain-like. For more practical advice on using metaphors and analogies, see Chapter 12.