13 Introduction

Group culture is one of the most powerful forces on the planet.

Not finance. Not strategy. Not technology. It is teamwork that

remains the ultimate competitive advantage,

because it is so powerful and so rare.

We have said it many times before, “data science is a team sport.” We get it, the data scientist is not a one-person show. They work with others, they are a member of teams and they work with other teams. We would like to think that putting highly skilled individuals together that great outcomes are predestined; the total is more than the sum of their parts kind of thing.

Just because people are highly trained and skilled does not guarantee that they perform well as a group. Many teams are highly dysfunctional and the total of their member’s contributions is less than the sum of their parts. Because teams are made up of human being, imperfect ones, teams are inherently dysfunctional (Lencioni 2002).

Understanding team culture and team dynamics is a first step in understanding how to build successful, highly performing teams. Teams are inherently dysfunctional, but they are not doomed. Ask any leader and they will remember fondly situations where they helped build or lead a highly functioning team. Being part of a team is much more enjoyable if the total contributions exceed the sum of its parts—but that does not come easy or for free.

13.1 The Spaghetti Tower

Coyle (2018) describes an experiment by Peter Skillman, known as the marshmallow challenge. A group is presented with the following resources

- 20 pieces of uncooked spaghetti

- one yard of masking tape

- one yard of string

- one standard-size marshmallow

The goal is to build with these materials in a limited amount of time (18 minutes) a tower that is as tall as possible with the marshmallow sitting on top.

The fascinating aspect of the experiments by Skillman is that different groups were asked to build the spaghetti tower and they performed very differently: CEOs, lawyers, business school students, and recent kindergarten graduates. In trial after trial, kindergartners built towers that were taller (26 inches) than the average tower (20 inches), handily beating lawyers (15 inches) and business school students (10 inches!).

Marshmallow challenges are routinely conducted and if you are reading this material as part of a course in data science, I hope that you get to experience it as well. The world record, it appears, stands at 65 inches. (Spoiler alert: following the link reveals how the tallest tower was constructed.)

Tom Wujec has conducted about 70 marshmallow challenges across the world, as he reports in his TED talk

Wujec explains that kindergartners are not only building taller towers, their structures are also more interesting. Are we suggesting to throw out architecture and engineering and build bridges, airports, and railway systems like kindergartners? No. Thankfully, the very tallest spaghetti towers that supported a marshmallow were built by architects and engineers. Phew.

But the experiment raises many interesting questions:

- Why were kindergartners so successful at building interesting and tall structures?

- What would the height of towers be if engineers approached the problem like kindergartners?

- Why were business school students under-performing? Is it because when you study business you somehow lose along the way the physics fundamentals a kindergartner easily commands?

There are a few reasons why the kindergartners outperformed the business students. They have to do with the approach to problem solving and how the team operates

Kindergartners start building without following a single construction plan. They try things and fail quickly, moving from one prototype to another prototype. They listen to each other and are ready to try out someone’s idea. They cooperate and offer each other help. They start constructing the tower immediately, wasting no time on figuring out how the team operates or who is in charge.

The business school students are taught to find the solution to a problem, to have a definite plan before implementing anything. Like the kindergartners they also went right to work. But rather than building, they examined the materials, thinking strategically, discussing options. They spend most of the 18 minutes developing the optimal plan on how to build the tower. Once they start the actual construction, they have no time to correct and start over if the plan turns out to be flawed. They also waste time on figuring out the rules of engagements (is it OK to criticize?) and their place in the group (who is in charge?): status management. What appears on the surface as a collaborative environment is actually a competitive situation.

As Coyle puts it

The kindergartners succeed not because they are smarter but because they work together in a smarter way.

The marshmallow is a metaphor for the hidden assumptions in a project. In this case, the assumption that a marshmallow is light and can be easily supported by a bunch of spaghetti. Many teams thus ignore the marshmallow until the end, when they place it on the tower as the last piece of the project. In reality, it turns out the marshmallow is quite heavy and placing it atop of a poorly constructed spaghetti tower can bring down the entire structure—at the very moment that should have defined success.

Every project has these hidden assumptions, the things you assume to be true without hesitation and without checking. Internet is available. Turning on the faucet dispenses water. The marshmallow weighs next-to-nothing. If what we take for granted does not come true, projects can fail spectacularly.

13.2 Dysfunctions of a Team

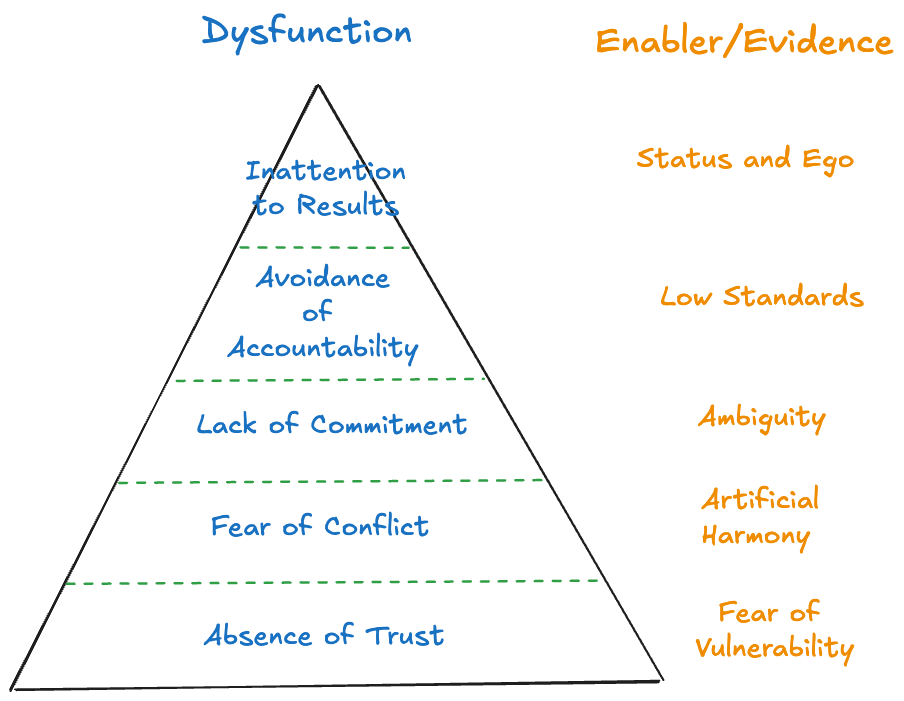

In The Five Dysfunctions of a Team, Patrick M. Lencioni tells the fable of a new CEO taking over a start-up company (Lencioni 2002). After observing the executive team for several weeks, she calls them to an off-site and introduces them to her analysis. She had noticed five dysfunctions in how the executive team was operating (Figure 13.2).

Absence of Trust. The failure on the part of team members to understand and open up to one another. This is not touchy-feely; great teams are honest with each others and are able to talk about their weaknesses, failures, and concerns without fear of reprisal. What gets in the way is our fear of vulnerability; the evidence of the dysfunction is invulnerability in the team.

Fear of Conflict. In the absence of trust, teams do not engage in open, honest and constructive conflict. The evidence of the dysfunction is artificial harmony and tension. Instead of engaging in honest dialog about issues and concerns, opinions are held back to preserve harmony. Veiled discussions and guarded comments result.

Lack of Commitment. Constructive conflict is important so that the team can develop a plan that everyone commits to and buys into it. When people cannot have their voices heard and their opinions considered, they will not get on board. It is not about getting consensus, it is about a culture to disagree and commit. The evidence of the dysfunction is ambiguity.

Avoidance of Accountability. Holding each other accountable to achieve the team goals, once there is clarity and buy-in about the goals, is difficult because team members are often peers. When people are not committed to the goals, they will try to avoid accountability (“I did not agree to this anyway”) and not hold others accountable. The evidence of this dysfunction is low standards.

Inattention to Results. This is the ultimate dysfunction: seeking out individual recognition and attention at the expense of collective results. The dysfunction thrives in environments without accountability. The results the team needs to achieve need to be so clear that no team member would consider actions that would only enhance their individual status or ego. Anything that diminishes achieving the collective goals makes the entire team lose. When it is ambiguous what the team is supposed to achieve as a collective, it is easy to fall back on focusing on individual success. The evidence of the dysfunction is concern about individual status and ego.

I was faced with building a leadership team in an organization that was used to a very different leadership style, where the team rarely met as a group. Instead, the CEO would have one-on-one conversations with the executives. After a re-org, some of those executives were now reporting to me.

Although I had not read the book by Lencioni at the time, I recognized all five dysfunctions in my direct reports. There was a lack of trust, folks did not engage openly with each others. There was a lot of politicking, positioning, and finger-pointing (absence of trust). On the surface, interactions were professional and cordial, covering the tension that existed between the teams (fear of conflict). There had not been a business plan for the entire organization, rather each team muddled along by themselves, setting its on goals in the spirit of what they thought was best for the company (lack of commitment and avoidance of accountability). The “first team” of the leadership members was their own organization, not the leadership team. Goals and results were set for their organization, quietly assuming that this would be for the benefit of the company as a whole (inattention to results). Status, ego, and standing with the CEO were currencies. Some team members did not see the other executives as peers, believing they should be given more weight because they were driving revenue, or were interacting with customers, or had more headcount, or …; fill in the blanks.

To make the leadership operate as a leadership team, a number of changes were put into place. Chief among them,

- Owning company goals together.

- Compensation plans that spelled out explicitly how variable compensation (bonus) achievement is tied to common goals and to individual goals.

- Treating all members of the leadership as peers by virtue of reporting to me, regardless of title or tenure.

- “Disagree and commit” policy. We argue as a team about best path forward, but when a decision is made, everyone defends the decision as if it had been their idea.

- No finger pointing rule. Instead of blaming your organization’s shortcomings on another team (“I could sell more if I had better product”), you have to offer your organization’s help to the other team, ask “how can I help?”

13.3 Three Questions

The performance of a team does depend on skill and experience of the team members. But those attributes by themselves do not guarantee a successful team either. It also depends on team culture. And as the famous management consultant Peter Drucker said

Culture eats strategy for breakfast.

If you do not pay attention to culture, your best strategy is toast. A toxic team culture diminishes team performance and makes us miserable.

Viewed from the outside, teams with great culture have an enviable chemistry that appears like magic. It is not magic, it is something that can be created, it is something that can be done. Strong cultures are built on interactions and our social needs. They have in common to offer a safe space where trust is built by shared vulnerability and a shared purpose.

Safety

Our unconscious brains are obsessed with psychological safety. Constantly worrying about whether we are safe in this group, where the dragons lie, whether we have a future with these people. We are looking for belonging cues that signal a safe space: eye contact, physical contact, being listened to, feeling invested in, feeling valued.

Once we feel safe, we can stop spending energy on worrying whether the social system rejects us and can focus on what the group is supposed to accomplish.

If you observe your own team or another team, ask yourself three questions:

Who talks? In high-performing teams, everyone talks and listens in similar proportions. Leaders do not occupy the conversation, they gather information from others.

How does information flow? Are side conversations (“back channels”) and conversations outside the team accepted and encouraged? Does information from those conversations flow back to the team?

How does communication work? Is there a lot of eye contact or are folks looking at their shoes when talking to each other? Do team members communicate with each other or does all communication go through the team leader?

There is a silly joke about the difference between introverts and extroverts. You can tell the difference between an introvert and an extrovert by observing which shoes they look at during a conversation. The Lencioni_2002introvert looks at their own shoes, the extrovert looks at your shoes.

Vulnerability

Vulnerability can have different meanings. A farmer is vulnerable to flood and drought, an endangered species is vulnerable to habitat loss, a first grader is vulnerable to bullying by someone in a higher grade. This type of vulnerability describes being in a state where one can be easily attacked or harmed.

Vulnerability is also an emotion that we experience during times of uncertainty, risk, and emotional exposure (Brown 2018). In Brené Brown’s words:

Vulnerability is not winning or losing. It is the courage to show up when you can’t control the outcome.

Why does vulnerability matter in the performance of teams?

Vulnerability is not about oversharing (TMI!) or disclosing details of one’s private life. It is about signaling that you are open to receive help and feedback, that you have weaknesses and that you are not clad with armor in your interactions. It is a powerful mechanism to break down barriers, to create connection, and to build trust.

Fake vulnerability does not work. It has the opposite effect, it breeds distrust. I once worked for a leader who was trying to manipulate with vulnerability: “C’mon folks, tell me what you think of my idea; I am completely vulnerable here.” Except, he wasn’t vulnerable, he was not open to input, and was only interested in affirmation of his idea.

Vulnerability sounds mushy, touchy-feely; it is anything but that. And it is most certainly not a weakness. Showing up when you cannot control the outcome is not a weakness. Standing in front of an audience to give a presentation is not a weakness. Waiting for the call from the doctor after the biopsy is not a weakness. Giving someone honest feedback that their performance is lacking and putting skin into the game to help them improve is not a weakness. Showing empathy when you inform an employee that they are not a good fit and

today is their last day with the organization is not a weakness.

The powerful aspect of vulnerability is its link to cooperation and trust. By sending a genuine vulnerability signal, the receiver is encouraged to send a vulnerability signal back and trust increases. A safe zone is established that allows sender and receiver to cooperate more freely. This loop is contagious and travels through rooms and teams.

If you observe your own team or another team, ask yourself three questions:

What are the openness signals? How is trust and cooperation established? Do you notice that it has been built in the past? How are new team members integrated into the group? Vulnerability signals can be subtle, an invitation to contribute ideas, a request for feedback, asking to “tell me more”.

How does feedback work? Giving and receiving feedback are very vulnerable moments. We try to please and avoid getting someone’s feeling hurt. We try to protect ourselves from judgment and rejection. During a performance review your manager tells you 36 things you did great and one thing you could improve on. It is that one thing you take away from the review and it bothers you to no end.

Is feedback given and received with care and empathy or is it given to establish hierarchy? Do team members acknowledge and act on feedback? Do team members feel safe bringing up ideas and how are these received?Are the boundaries understood? Vulnerability does not mean anything goes, anything can be said, and any behavior is tolerated. Does everyone know what is okay and what is not okay?

Purpose

When working with teams I often asked them three questions to learn about their purpose:

What is your product? The product can be a customer-facing item or an internal deliverable. There should be some form of output that the team can point to: “This is what we do!” Even if the purpose of a team is to develop ideas, the ideas are the product. If you do not produce anything, what is the purpose of doing what you are doing?

Who is your customer? Every team works for someone or something. How is the product picked up and what happens to it afterwards? If the product falls on the floor and nobody picks it up, what is the purpose of doing what you are doing?

What does success look like? How do you measure whether you and the team performed adequately, below, or above expectations? What are the expectations?

If you find yourself on a team that is unsure about what it is they are working on, not clear who or what it is for–if anything, and it is not clear what a good job looks like: get out!