3 Storytelling

When communication in data science works, we call it data storytelling.

3.1 What is a Story

Everybody wants to be a storyteller. I admit that NBC’s The Voice is one of my favorite TV shows. When the judges respond to a contestant’s performance they are often praised as storytellers.

Telling stories is widely accepted as the most effective, persuasive, and influential form of communication. Stories help us learn and remember by connecting us emotionally to the narrative.

What is a story, what is storytelling, and why is it effective?

A story is a narrative with a beginning, a middle, and an end. This is also described with the ABT formula in Oliver (2023):

- A, the beginning: “And this is the way things were”

- B, the middle: “But there was a problem”

- T, the end: “Therefore this is how it resolved”

In addition to the ABT story arc, a story has

- one or more characters to engage with

- a place and time we are transported to

- a plot (what, when, where, why, to whom is this happening)

- a conflict and a transformation through conflict

- a resolution

Many data scientists believe in the old adage that

A picture is worth a thousand words.

and, as a result, assume that presentations high on visual content will automatically resonate with the audience. Not so. While visual aids are often more effective than text, tables, and bullet points, by themselves they are not sufficient to create memorable content. And, it often does not take 1,000 words to communicate something. Fewer words, carefully chosen, can create memorable content because they tell great stories.

In fact, you might not need many words at all to tell a great story. Check out this visual essay about gun deaths in the U.S. in 2018. It has many of the ingredients of a great story. Can you identify beginning, middle, end, characters, place, time, plot, and conflict?

The elements of a story listed above are the ingredients for your recipe. Just like visualizations by themselves are not stories, using the ingredients does not guarantee a well-told story. Having ingredients does not imply a well-cooked meal. The tools of storytelling are not the same as the art of storytelling.

3.2 Why are Stories Effective

We have seen in Chapter 1 that Aristotle said effective oratory has three appeals, logos (the logical arguments, the facts), ethos (the credibility), and pathos (eliciting an emotional response). The human brain processes information through emotions, information is meaningful when it evokes emotion. Storytelling connects us emotionally to the narrative; that is why it is so effective.

As social animals we tend to adopt the positions of those to whom we have a strong social connection. Endorsing the position reinforces the connection to others with whom we share important commitments.

In his brilliant TEDx talk about the magical science of storytelling, David JD Phillips asks

How is it possible for you to be so easily tricked by something so simple as a story?

Watch for yourself:

To summarize the content of the TEDx talk:

We started developing language about 100,000 years ago, long before we invented cave paintings (~27,000 years ago), text (~3,500 years ago), or PowerPoint (1987). Our brains are wired to transferring knowledge through storytelling more than any other format.

David Phillips describes the “angels’ cocktail” of three hormones that are induced into our brains through (effective) storytelling:

Dopamine. Dopamine is also called the “feel-good hormone”, it is involved in motivation and deciding whether to engage. Higher levels of dopamine increase focus, attention, creativity, and memory. You increase dopamine in your audience by creating suspense in your story, making the audience wait and expect. When we are waiting and anticipating, we are paying attention.

Oxytocin. Oxytocin is also called the “love hormone”, it is produced when we form relationships and during sexual activity. The effects of greater oxytocin level is to bond, trust, and to become more generous. It makes us feel more human and more relaxed. In storytelling you increase oxytocin in the audience by creating empathy in the characters. E

Endorphins. Endorphins have the effect of relieving pain, reducing stress and anxiety, and make us feel good. An effective way to create endorphins is to make people laugh. They become more focused, relaxed, and creative.

Brain researchers describe a mind meld between teller and listener during storytelling. It is not as if the two brains act as one, but more like the brain activity patterns seen in the storyteller are mirrored in the listener, whether there is one listener or many. And the more similar the brain patterns are, the better the transfer of memories.

In telling the stories in the TEDx talk, Phillips combines the tools and ingredients of storytelling with the art of storytelling to connect with the audience.

3.3 Storytelling Models

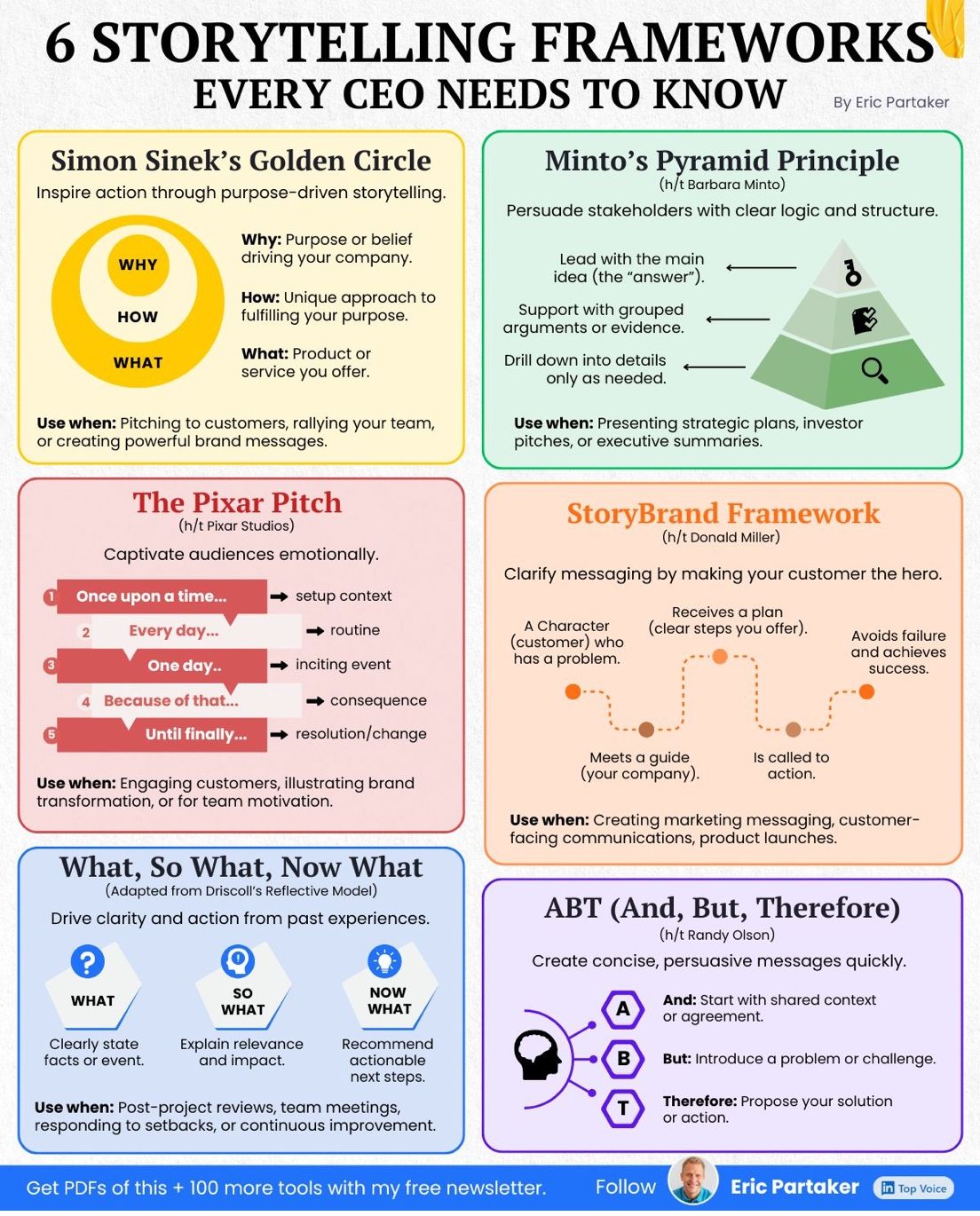

We mentioned the ABT formula at the beginning of the chapter. This is only one of many models (or frameworks) to tell a story. Figure 3.1 shows five additional approaches to crafting a story.

The Golden Circle refers to a concept promoted by Simon Sinek in one of his famous TED talks and in his book “Start With Why”. You can watch a video of the talk at the link below. Sinek argues that too often we communicate from the outside-in, starting with What we are doing, then explaining How we are doing it, and only then getting to the reason behind it all, the Why. Effective communication works from the inside-out, starting with Why we are doing what we are doing–the thing or purpose that drives us.

A common element of these storytelling models is to make an emotional connection early in the communication process:

The Golden Circle. If you lead communication with your purpose, your just cause, the reason why your organization (or you) exist, you communicate from a place of passion and meaning that gives communication credibility (ethos) and pathos.

Minto’s Pyramid. By starting a pitch with the answer, the main point, you get the attention of the audience.

ABT. By starting with shared context you are operating at the same level as the audience. The Pixar pitch does the same by describing a world and setting up a context with “Once upon a time…”.

StoryBrand. You lead with a customer problem, making the issue personal and relatable.

3.4 Data Storytelling

How does the neuroscience of storytelling, the dramatic arc and storytelling principles such as place and time, characters, conflict, transformation, and resolution map to communication about data? Do I need to weave all this around the pie chart I need to talk about?

There are two important variations of data storytelling for us:

Storytelling with Data. Here we use data to craft a compelling narrative. When journalists do this it is called data journalism. You also encounter the term visual essays.

Storytelling about Data. Here we use storytelling principles to create a compelling story about the results of data science.

Visual Essays

Here are some great examples of data journalism and visual essays, using data to tell a powerful story.

The next three examples are curated by the company Shorthand which develops tools for data storytelling. (Scroll down in the browser to unfold the stories).

Brexit by the Numbers. A Sky News story of the immediate impact of Brexit on the UK.

The annual impact report of Oxfam Ireland, a world-wide development organization fighting against inequality, poverty, and injustice.

The Arab News story about Jews of Lebanon, using simple graphics to tell the story of a minority community.

As you scroll through these publications, ask yourself

- What do these presentations have in common?

- Why is a particular presentation effective or ineffective?

- Which graphical elements are being used?

- Can you identify components of the dramatic arc and storytelling principles?

For twenty great examples of visual essays and visual storytelling, check out this collection.

A particularly powerful–in my opinion–data story is being told with a single graph style in this story about gun deaths in the U.S. It was introduced earlier in the chapter. If you revisit the visual essay now, can you also identify the emotional appeals of the story and how it helps you connect to the material?

Telling Stories about Data (Science)

Comnbine visuals and language

Recall that our brains are most wired to knowledge transfer through language, followed second by knowledge transfer through images. Combining visualization with language allows you to craft compelling stories that unlock the meaning of what you wish to convey.

Beautiful graphics are an element of a data story, but cannot by themselves provide the context in which the meaning is unlocked. They are part of the story. The production value of graphics and slides does not translate to a good story in itself.

You are using language and visualizations to make connections. What you say and what you show are not the story in itself. The audience will not remember the particular graphic. The audience will not remember the layout of the slides. But they will remember the characters in your story.

Focus on the audience

This is trivial but it bears repeating. You are presenting material for the benefit of the audience, not for the benefit of the data science team. Go back and read that sentence again.

Everything you do should be focused on how to connect with the audience and make them memorize the meaning of your content. So you do not talk about the data science team and its accomplishments. It is not about you, it is about them! You talk about what the material you present means for them.

It is OK to acknowledge the team at the end of the presentation, possibly in appendix material that is shared with the presentation but not displayed in the room.

Pay attention to how many presentations start with “This is Me”, “This is Who we Are”, “This is What we Do”, “These are our collaborators”. You do not ever want to take credit for things you or the team did not do and you do not ever want to take credit away from others. The beginning of the presentation is not where you do that, however.

The counter argument that is sometimes made is that the audience has a limited attention span and putting credits and acknowledgements at the end buries them. By the time you get there the audience is exhausted and that misrepresents the team’s hard work and accomplishments. Also, if you run long you might not get to that part of the presentation.

Two responses to this counter argument:

The value of the work and the accomplishments of the team need to be evident from the content you are presenting.

If you are not getting through the material you need to work on the presentation. Not getting to material is the wrong kind of cliffhanger for the audience.

Create engagement

The modern office or classroom environment is not at all like sitting around a campfire at night. There are glass walls, people moving around, a clock in the corner of the room, HVAC systems going on and off, distractions from devices. On the plus side, you are not worried about being distracted by a saber-toothed tiger.

Starting a presentation by talking about process and methods, and introducing the team is a good way to lose the audience early on. You will have to fight against the current to re-engage them. Remember the ABT formula:

- And this is the way things were

- But there was a problem

- Therefore this is how it resolved

Get right into it.

To draw the audience in, use relatable experiences and frame them in the language of “you” and “yours”. Stimulate curiosity by raising an open question or mentioning a surprise result. Instead of opening with a slide titled “Fourth Quarter Cloud Expense Forecast” consider opening with these statements:

A look at our recent data suggested costs would increase. But did they?

Do cloud expenses really affect the bottom line?

Do the data support the conventional wisdom of subscription model vs pay as you go?

When I saw the data I was reminded that I never again want to wait in line

When sharing your own experiences, you are drawing on yourself as an example. Avoid oversharing and just talking about yourself.

The audience will be drawn to you if you are passionate and having fun working on this problem. It engages their curiosity, wondering what it is about this topic that makes you so passionate. The interest in the topic rubs up on the audience. Avoid any extremes. If you are too serious or dispassionate the audience might perceive that there might be deep-rooted issues with the material. If you are goofy or joke too much you will be seen as not serious and lacking credibility.

Story helpers

How do you go from having the statement

We are predicting a 7% increase in revenue in the next quarter

to having a story?

Anecdotes

Anecdotes are short, relevant, personal accounts of something relevant. The anecdote should be short enough not to distract from the story and long enough to be interesting. If you are telling a story about customers failing to sign up for the paid subscription service after a trial period, you could tell an anecdote about how you recently decided to use an online service because you could create the account through an existing service rather than creating a new username/password combination that you are loathe to track.

Case studies

A case study explains how a problem led to a solution. The case study does not have to present the identical problem as the one you are telling a story about. It just has to be a relatable study that suggests a possible solution path. Case studies are useful if the audience has experience with problems like those addressed in the case study.

Examples

Examples are similar to case studies, except they do not necessarily lay out the challenge or the solution. They can relate the audience to what other organizations are doing. Examples help convey that you are not solving an isolated or unusual problem and others are thinking about it as well.

Scenarios

A scenario is when you lay out a series of events and you ask the audience to predict each outcome. Scenarios are hypothetical and help get ideas out into the open. Make sure that the scenario is not too simple, otherwise it sounds like a children’s story. Like anecdotes, scenarios work best at the beginning of the story and should be told in the third person—you are not relating a personal experience:

Imagine a customer wants to move from the trial experience to a paid subscription. They like the ease with which they can flip the account but are hesitant because they have heard that it is a hassle to discontinue the service in the future.

Anecdotes, case studies, examples, and scenarios are not stories in themselves. They help you weave your story and give the larger message more meaning.