library(arules)

data(Groceries)

summary(Groceries)transactions as itemMatrix in sparse format with

9835 rows (elements/itemsets/transactions) and

169 columns (items) and a density of 0.02609146

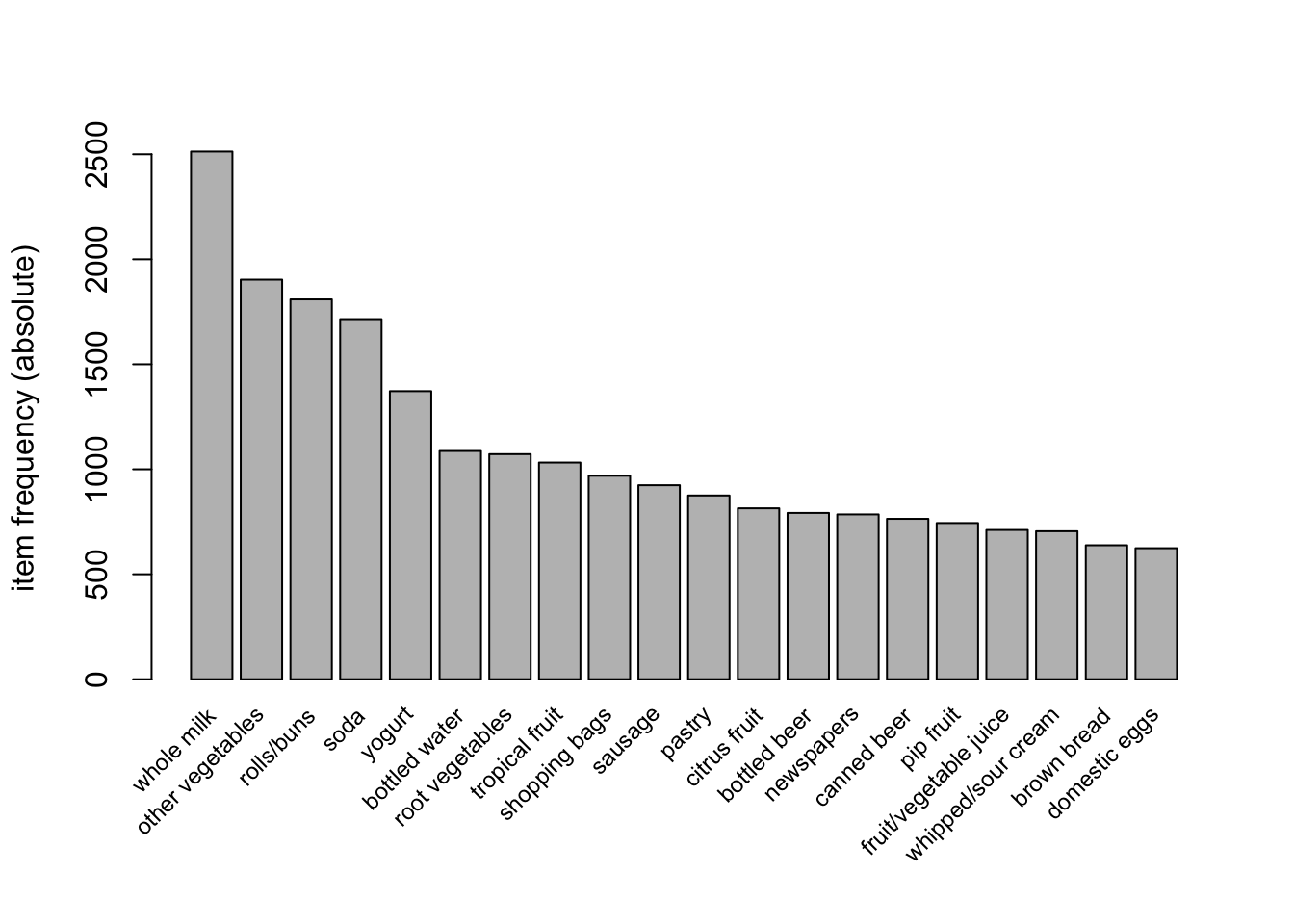

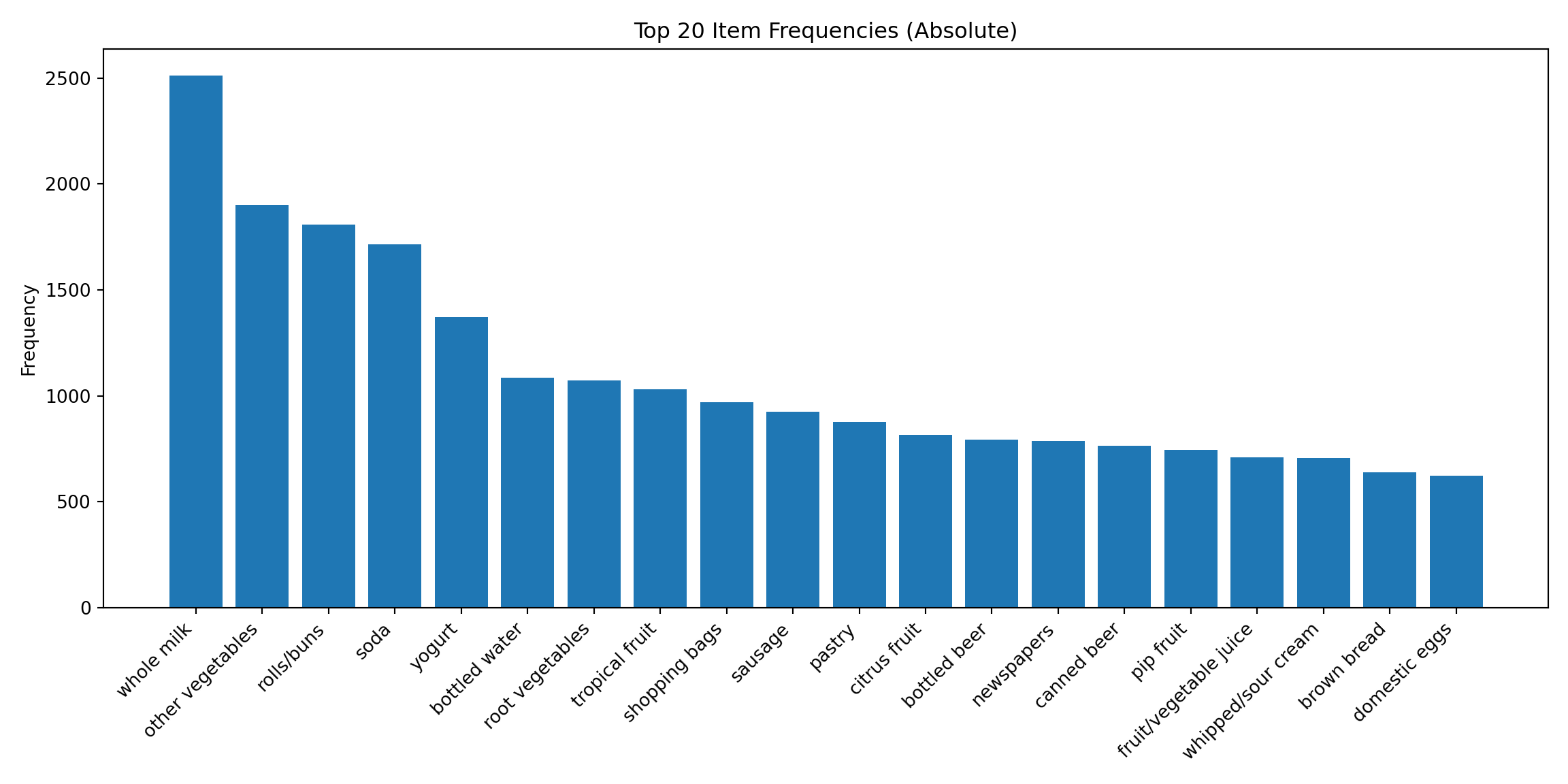

most frequent items:

whole milk other vegetables rolls/buns soda

2513 1903 1809 1715

yogurt (Other)

1372 34055

element (itemset/transaction) length distribution:

sizes

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

2159 1643 1299 1005 855 645 545 438 350 246 182 117 78 77 55 46

17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 26 27 28 29 32

29 14 14 9 11 4 6 1 1 1 1 3 1

Min. 1st Qu. Median Mean 3rd Qu. Max.

1.000 2.000 3.000 4.409 6.000 32.000

includes extended item information - examples:

labels level2 level1

1 frankfurter sausage meat and sausage

2 sausage sausage meat and sausage

3 liver loaf sausage meat and sausage