54 Personal Information and Personal Data

54.1 Privacy and Confidentiality

Working with data requires compliance with data privacy regulations, an increasingly complex field. It is our job to safeguard all information, not just information about individuals. In the everyday use of the words, we might not make a distinction between privacy and confidentiality. Legally, and technically, there is an important distinction. Privacy is about people; it is about the individual’s rights regarding their information. Confidentiality is about an individual’s data and how it is protected from others.

Confidentiality can be required explicitly: confidentiality clauses in employee agreements can limit information we are allowed to share about our employer. In the course of employment, we are learning trade secrets and proprietary information about products that constitute a competitive advantage. Data collection in research projects follows detailed protocols to ensure integrity and trust in the information. Non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) place restrictions on information that can be shared.

Besides explicit confidentiality agreement, there is an expectation of confidentiality beyond privacy. Many consumers understand that organizations have access to their data. Their concern is how the organization uses the data, and ensures that it remains a secret. An organization that meets the letter of data privacy regulations can still run afoul of the confidentiality expectations of its employees and customers.

The Code of Conduct of the Data Science Association has this to say about confidential information:

Confidential information is information that the data scientist creates, develops, receives, uses or learns in the course of employment as a data scientist for a client, either working directly in-house as an employee of an organization or as an independent professional. It includes information that is not generally known by the public about the client, including client affiliates, employees, customers or other parties with whom the client has a relationship and who have an expectation of confidentiality. The data scientist has a professional duty to protect all confidential information, regardless of its form or format, from the time of its creation or receipt until its authorized disposal.

Confidential information is a valuable asset. Protecting this information is critical to a data scientists reputation for integrity and relationship with clients, and ensures compliance with laws and regulations governing the client’s industry.

…

A data scientist shall protect client confidential information after termination of work for the client.

A data scientist shall return any and all confidential information in possession or control upon termination of the data scientist—client relationship and, if requested, execute an affidavit affirming compliance with obligations relating to confidential information.

Special safeguards and regulations apply to personal data and personal information—information that is about people or relatable to people. This is the realm of data privacy. Not safeguarding personal information can lead to harm for both sides: identity theft, fraud, violation of rights, etc., for the individual whose personal data is mishandled; fines, legal action, loss of license, embarrassment, loss of business, etc., for the individual mishandling the personal information.

Example: Henrietta Lacks and the HeLa Cell Line

Henrietta Lacks was born on August 1, 1920, in Roanoke, VA (Figure 54.1). She is probably one of the most important medical pioneers of the 20th century, with contributions that study the effect of toxins, drugs, hormones, and viruses on the growth of cancer cells. Not through her own medical work, but through the cells that were taken from her—without consent.

Mrs. Lacks had moved to Maryland and in 1951 visited Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore complaining of vaginal bleeding. A malignant tumor was found on her cervix, and she started radiation therapy. On October 4, 1951, the cervical cancer took her life.

Cancer cells retrieved from her through a biopsy were sent to the tissue lab of Dr. George Gey. To his astonishment, Dr. Gey found that Mrs. Lacks’ cells behaved differently than cancer cells from other patients. While other cells would die within days of culturing, Mrs. Lacks’s cells continued to live and doubled about once a day.

The cells, called the HeLa cell line, is the first immortalized human cell line and continues to live to today. It has been used in countless medical research projects. As was practice at the time, no consent was required from the patient to culture the cells, and to distribute them. This would be unthinkable today. Even so, it was an unethical practice back then.

After her death, Dr. Gey instructed his lab assistant to collect more cells while her body was in the autopsy facility.

Johns Hopkins claims to have never sold or profited from the HeLa cell line and has given them away freely and widely for scientific research. Johns Hopkins admits that it could have done more to work with the Lacks family. They were not informed until 1975 about the existence of the HeLa cell line—another disturbing aspect about handling medical information without consent. The Lacks family found out about the cells because researchers contacted them and asked for blood samples hoping to use those to distinguish HeLa cells from other cell lines and through a conversation at a dinner party.

More than 10,000 patents involve HeLa cells. They were used to develop the polio vaccine, and in everything from AIDS research to gene mapping to testing cosmetics.

In October 2023, a statute of Henrietta Lacks was dedicated at Lacks Plaza in Roanoke. Small-scale statutes were dedicated at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at VTC, Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, and Carilion Clinic. HeLa cells live at Fralin Biomedical Research Institute and in labs all over the world.

54.2 Data Privacy Regulations

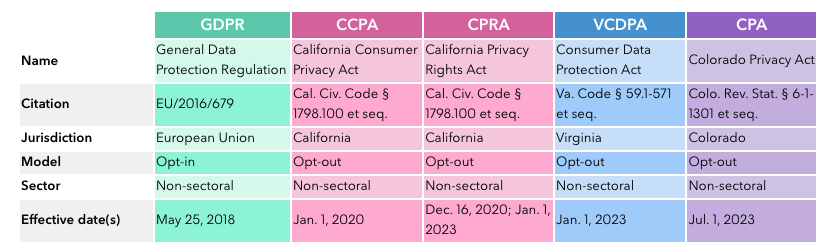

Since the late 2010s, data privacy regulations have appeared in many parts of the world. They are often similar but frequently different enough to create a messy landscape of laws that can be difficult to navigate. The most important regulations are

GDPR: the General Data Protection Regulations of the European Union

CCPA: the California Consumer Privacy Act

CPRA: the California Privacy Rights Act

VCDPA: the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act

CPA: the Colorado Privacy Act

This article in Bloomberg Law provides a good overview of the four pieces of legislation.

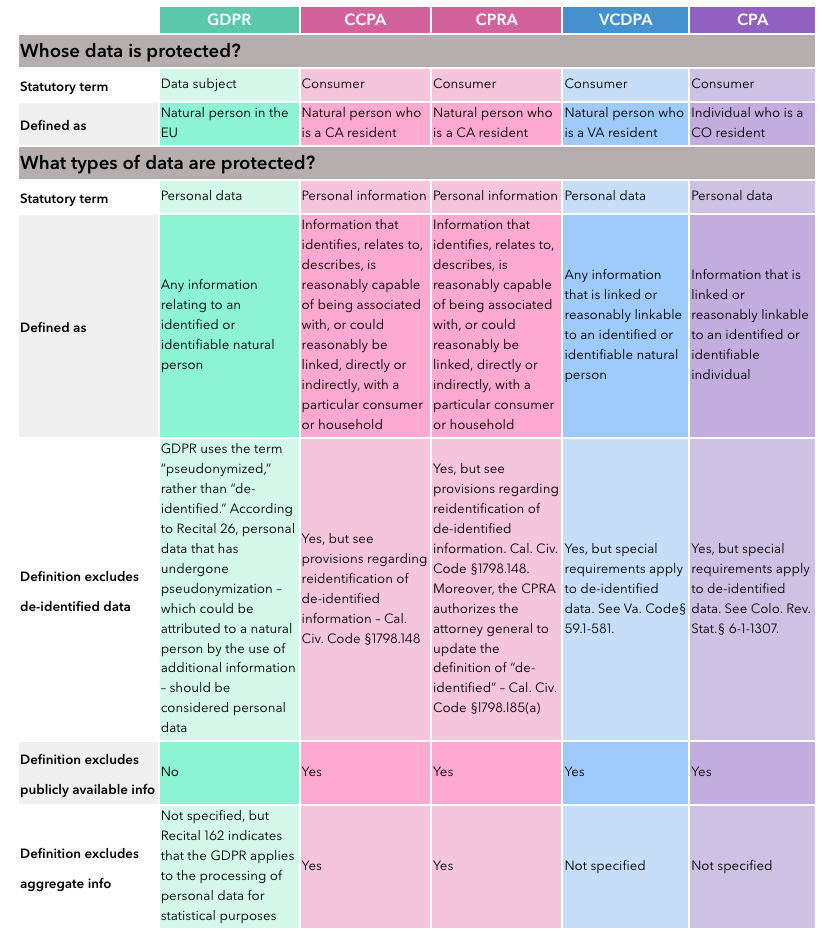

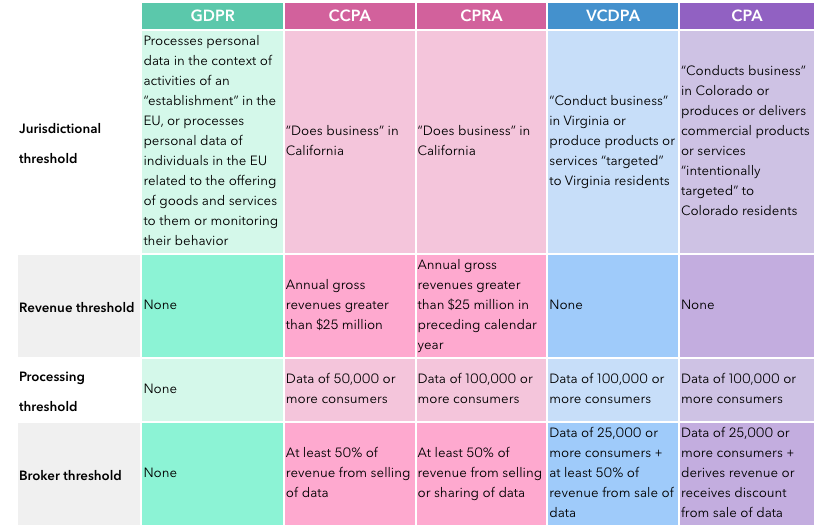

There is substantial overlap between the regulations, and also important differences. For example, the U.S. laws, which are based on bottom-up common law, are opt-out laws, whereas the top-down GDPR is an opt-in law. Consider consent, for example. An opt-out law assumes that consent is automatically given unless someone opts out. Under GDPR, consent is automatically withheld unless someone opts in explicitly (Figure 54.2).

The type of personal data protected under the regulations differs as well. The California statutes extend personal data to data about a household. When modeling consumer behavior, for example, modeling at the aggregate household level does not relieve you from worrying about personal data privacy of California residents. The U.S. laws exclude publicly available data from the definition of personal data, while GDPR includes publicly available data (Figure 54.3).

54.3 What is Personal Data?

Things get complicated quickly because the definition of personal data varies and because there are many regulations to pay attention to. The General Data Protection Regulations (GDPR) of the European Union applies a very broad and non-prescriptive definition of personal information. HIPAA, The U.S. Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act defines items specifically as PII, personally identifiable information. The primary focus of HIPAA is to protect personal information related to health. The National Institute of Standards and Technology, NIST, applies a different definition to PII. For example, your computer’s IP address is not PII under NIST standards but is personal data under GDPR. In 2011, the California State Supreme Court ruled that a person’s ZIP code is PII. The California Consumer Privacy Protection Act (CPPA) distinguishes personal information such as internet browsing history from sensitive personal information, for example, an account log-in or union membership.

We can never cover all the bases and thus recommend taking a conservative stance and a broad definition of personal information. If in doubt, consider a piece of data that can be linked to a person as personal information that is protected and needs to be safeguarded. The broad coverage of GDPR is a good place to start. In addition, you need to know the data privacy regulations that apply in a particular domain or to data from a specific group. The following are some federal laws that g overn specific types of data:

The Privacy Act of 1974 governs how federal agencies can collect and use data about individuals in its system of records.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accounting Act (HIPAA) governs the collection of health information.

The Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) governs the collection of information about minors.

The Gramm Leach Bliley Act (GLBA) governs personal information collected by banks and financial institutions.

The Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), which regulates the collection and use of credit information.

The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA), which protects the privacy of student education records.

The GDPR defines personal data in Article 4:

‘personal data’ means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (‘data subject’);

There is a lot to unpack here. What does “relating to” mean? What is the difference between an “identified” and an “identifiable” natural person?

An identifiable person can be identified by reference to a name, ID, location data, or by one or more other attributes specific to the identity of that person, such as genetic, mental, physical, cultural, or social information. To be identifiable, it is sufficient that you can distinguish them from other individuals. Personal data is not just what makes us unique, it is sufficient for the data to distinguish us from others. Your online shopping cart makes you an identifiable person because it can be used to distinguish you from people with a different shopping cart. It does not matter that there could be other shoppers whose cart looks exactly like yours.

The name is an identifier, but it might not make you identifiable—there are many “John Smiths”. It is still personal information.

What is the meaning of “relating to”? A careful reading of the GDPR definition of personal data suggests that identifying data might not be personal data if it does not relate to the person. Wait, what? A few examples will make this clearer:

Information about an individual or about their activities is obviously personal data, it explicitly relates to the individual. Your birthday is your personal data. However, March 28, 2003, is just a date. It is not personal data until it is someone’s birthday, anniversary, wedding day, arrest day, etc.

Consider a job listing that includes salary information. The salary is not personal information, it relates to no specific individual. As soon as the position is filled, the salary information becomes personal information because it now relates to the new employee.

An organization has an org chart with job titles. The job title in the org chart is not personal data until it is related to a specific individual or a group of employees.

Data about a house is not, by itself, personal data. But an individual’s tax record or utility bill are personal data. As soon as the information about the house is tied to an owner, it becomes personal data—it now relates to the owner. You can conduct analyses of house values in a geographical area. The houses in the study are selected because of their properties—four bedrooms and a double garage—not because they are occupied by a specific entity. But if the data about the house is used with respect to an individual, then it is personal data.

A factory collects information about a machine on the factory floor. This is not personal data if the purpose of analysis is to understand the operating characteristics of the machine. If the data is used to assess the productivity of the machine operator, then it is personal data.

The definition of personal data in GDPR is non-prescriptive. The regulations do not explicitly state that a social security number is personal information—it is. Whether information is personal data depends on the context. Does it relate to distinguishable individuals? If so, it is personal data. GDPR is adaptable because of this approach, if we determine that an IP address is personal data in a context, then a MAC address is as well. The downside of a non-prescriptive definition is that context matters, and we need to know how to apply it.

Data does not have to be correct to constitute personal data. A social-security number entered into a database is still personal data, even if someone fat-fingered some digits.

Example: Inaccurate Personal Data

John and William live in an apartment building; John lives on the ground floor and William lives on the top floor. They both wear glasses.

The landlord receives a complaint that the man wearing glasses who lives on the ground floor has engaged in bad behavior. However, the complaint actually is about William’s activity.

The landlord records the information about the behavior relating to John. The information is inaccurate, but it is nevertheless personal data related to John. At the same time, this is also personal data about William, even though it has been recorded about John.

54.4 Safeguarding Personal Information

If you google how to safeguard personal information you get a wealth of similar responses—almost all of them are about how you can safeguard your personal information: use strong passwords, use two-factor authentication, don’t overshare online, turn off location services, watch out for phishing attempts, do not follow unknown or suspicious links, keep your social security card in a safe place at home, …

But how do we safeguard other’s personal information that makes it into data sets we work with? There are a number of principles you can follow as an ethical data scientist. These (and more) are enshrined as the data protection principles of GDPR.

Lawful, Fair, and Transparent

Act in the best interest of the data subjects, always on a legal basis and with best intentions. That means you had consent to collect and analyze the data and the scope of analysis does not exceed what can reasonably be expected.

Data Minimization

Only collect and keep the amount of personal data that is needed, in terms of the number of records and the number of variables. If you gather data to deliver a newsletter electronically, then all you need is the name and email address. Maybe you do not even need to know the name of the subscriber. Having their job title might be an interesting piece of information but it is not necessary to send out the newsletter—it should not be collected.

Suppose you analyze data on houses to develop a predictive model for residential real estate prices, and the data set contains information about the owners of the properties. This information is not necessary for the purpose and should be removed from the data frame you work with.

Confidentiality

Only people who should have access to data are working with the data. If you are in control of data, you have a responsibility to protect the personal data you are processing. A common means of violating this principle is sharing data with others not knowing that the data contains personal information. If you receive a request for access to data that you have access to, ask yourself whether the requestor is authorized to use the data. If in doubt, put security concerns ahead of trying to be helpful.

Storage Limitation

Do not store personal data you do not need anymore. This is related to the data minimization principle, do not keep what you do not need.

Destroying data is trickier than you might think. There can be multiple copies of records, on multiple devices, including backups in the cloud, backups on tapes, etc. The same information can be stored at different levels of data preparation, for example in different layers of a data lake with medallion architecture. You can destroy data by removing it from storage devices using erasure, degaussing (destroying the magnetic field), or overwriting. Or you can destroy the storage device, for example by shredding hard drives.

The GDPR include a right to data deletion, any data subject can ask that their personal data be deleted. You need to know what personal data you have on someone, where it is, and how to destroy that data.

If you gather email addresses for the purpose of sending an electronic newsletter, and you decide to stop sending newsletter, you have to delete the email addresses because the purpose for which the personal data was given no longer exists.

Purpose Limitation

Use the data only for the purpose it was intended for. If the purpose expands or changes you need to re-secure consent. You cannot reuse personal data for other purposes. If you tell an online user that you store their IP address to document their consent, then you cannot use the IP address to send them marketing material.

Anonymization and Pseudonymization

Anonymization: remove personal information from a data set. The anonymized data should eliminate direct re-identification, for example, by combining other information in the data set.

Pseudonymization: pseudonymizing data is a weaker safeguard than anonymizing it. Pseudonymization replaces the original value of personal information with a mask or by encryption. If the pseudonymization is reversible, for example with an encryption key, the data is still considered personal information.